All major problems have many sides and components. The importance of anthropology in environmental issues is to consider different perspectives of cultures and identities of the entities involved to gain a more accurate understanding of the nature of the problem. Environmentalists are often middle to upper class people of Western tradition and will often perceive these problems and their possible solutions from a Western frame of reference. This may exacerbate these problems due to misunderstandings of the culture and perspectives of the local inhabitants, local government, and local traditions, among other things, and the solutions proposed may not be ideal.

To get us started, we will establish a few methods of examining a culture and its impacts on the environment: cultural ecology, ethnoecology, and scientific. In short, cultural ecology and ethnoecology are both the study of the relationship between culture and ecology. Their main difference is that cultural ecology examines the culture to extrapolate and deduce its roots in its environmental surroundings, where as ethnoecology emphasizes understanding the culture’s framework of knowledge and how they perceive they are tied to the environment, within their own narrative. The scientific approach is instead interested in raw data, which help to ground the research, as shown by Fairhead & Leach.

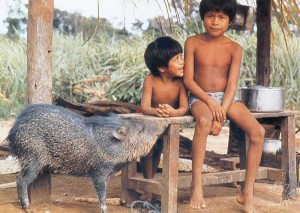

Each of these approaches have their flaws, so it is appropriate to consider more than one approach to more accurately see the whole picture. Cultural ecology paints a broader picture in broader strokes and is more of an outsider perspective, whereas ethnoecology is an attempt at an insider perspective. I think ethnoecology is very important to an in-depth understanding different perspectives and studies under this discipline have shown that different cultures can hold vastly different frameworks of knowledge, much to the ire of knowledge objectivists. One example is that of Aparecida Vilaça’s work with the Amazonian Wari people, who have a vastly different concept of body and spirit, and their relationship with nature, than that of the West. Understanding these things will allow much smoother and more effective communication of ideas between environmentalists and the local inhabitants. The main problem with ethnoecology is that it can be easy for one to get lost within a culture’s local knowledge system and fail to see the bigger picture. On the other hand, the scientific approach may not be as objective as it seems, as evidenced by Melissa Checker’s work with the residents of Hyde Park in Georgia.

Environmental policies may be passed on a governmental level, but there are many factors that affect how it is implemented. It is important to understand how different people perceive their connections to the environment around them, and it is also important to understand their motivations and needs. Without a clear understanding of these things, it may prove hard to motivate genuine local environmental action. In many cases, such as that of Nora Haenn’s work with campesinos living in the buffer zone of the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, or Melissa Checker’s work, referenced previously, it was only when the goals of environmental scientists and local inhabitants aligned that resulted in actual willing action. In both cases, the environmental scientists, government agents, or other people in positions of power failed to consider and adequately account for the local knowledge of the inhabitants and their perspectives, needs, and desires, and in both cases, were met with varying degrees of disastrous results. Thus, we must consider these things to gain a better understanding of the problems associated with the palm oil industry, and how to best deal with them. Additionally, the problems within palm oil industry is contributed to by a number of cultural, economic, and global demand factors. This concept is best explored by Anna Tsing’s idea of “friction.”

Finally, before we continue, we must also address how our own personal identities come into play. Our identities color our own perspectives of the world, so we must take a moment to recognize our own identities and how it may affect our judgment and interpretations of environmental issues. As a Westerner viewing from the framework of Anthropology, we may be unconsciously tempted to assign the things we learn about another culture to fit within one of our own learned narratives. We must attempt to produce cultural reports that are, to our best efforts, as unbiased as we can. We must attempt to remove ourselves from our personal cultural frameworks that we are accustomed to and accurately represent the data we collect, and prevent others from misusing the data. J. Peter Brosius presents an interesting case in which his own research with the Penan people of Borneo was misrepresented by environmentalists who sought to further their own agendas by attempting to fit his research within a popular and likable social narrative of indigenous spiritual wisdom. This is a great reminder that we must be anthropologists, not caricatures of one.